On Saturday, I took a Bookmaking for Beginners workshop taught by Sarah Smith through GSLIS Continuing Education. The workshop began with a short lecture about different kinds of bindings through history, and how contemporary artists are re-using and making books. The rest of the day was all hands-on: we started with the one-sheet fold-up and the accordion structure, then the blossom fold, Turkish map fold, and Korean map fold; then we learned how to make single-section and two-section pamphlets, and finally how to do chain-stitch.

All the books! From top to bottom: Blossom fold, Korean map fold, accordion fold (with covers), woven flexagon, Turkish map fold, two-section pamphlet, one-section pamphlets, chain-stitched binding.

From left to right: two-section pamphlet, one-section pamphlets (3- and 5-station), and Korean map fold.

This is the Korean map fold book: it’s the same one that looks like a little cedar block in the previous picture. It’s bulky because it contains six pieces of 8.5″x11″ paper, folded into 8 sections each.

This is the two-section pamphlet; the sections are each made up of four sheets of paper, each folded in half once. The cover has a pleat in the middle, and there are three “stations” (holes) where the waxed thread goes through all the layers to hold it together.

This is a one-section pamphlet, also with three stations. I gave the other pamphlets rounded corners, but I folded the edges of this cover in, so it has French flaps (like fancy trade paperback editions sometimes do).

All four pamplets: the top two have five stations, the bottom two have three.

Standing up like this, these remind me of The Monster Book of Monsters from Harry Potter (when Hagrid teaches the Care of Magical Creatures). On the left is the blossom fold; on the right, the Turkish map fold.

Here’s the Turkish map fold, open. It does fold down nice and flat – I think I have a city map of Paris folded in a similar way.

This has the best name of all: woven flexagon. We started with one long sheet (the cream-colored paper), and used a blade to make slices about 1″ apart; then, we took the colored papers and wove them between the slices. It’s quite cheerful-looking, but I have no idea what I’ll do with it.

A simple accordion fold, with covers made of binder’s board covered with decorative paper. We got to use polyvinyl acetate (PVA), an archival-safe plastic adhesive, to glue the paper cover over the board. Sarah showed us how to tuck the corners in with a bone folder to make them smooth and sharp.

The same book, lying open. I preferred the sewing to the folding; I couldn’t make the folds 100% exact. Sarah also showed us how to make an accordion fold with pockets, which I would have liked to cover with the binder’s board, but mine didn’t quite stack straight.

Finally, the chain stitch – this is the longest book, with five sections, or signatures, sewn together.

Here’s the chain-stitched booklet, closed. The stitching makes a nice pattern.

Other than being pretty, the chain stitch is also a nice binding because it allows the book to open flat, which is good for journals and sketchbooks, because you can write or draw deeper into the margins without worrying about the gutter.

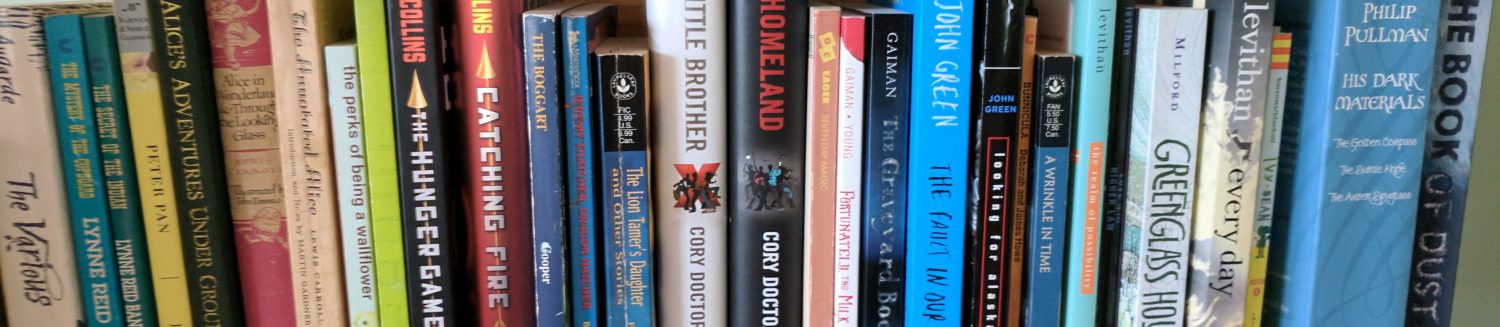

All the bindings!

A flock of books – all hand-made in less than seven hours. Even though I probably won’t be using these bookmaking skills in a practical setting anytime soon, the workshop was a good experience: I learned new things, stretched the part of my brain that relates to making tactile things, and created a physical product to use or give as gifts. All in all, a Saturday well spent.