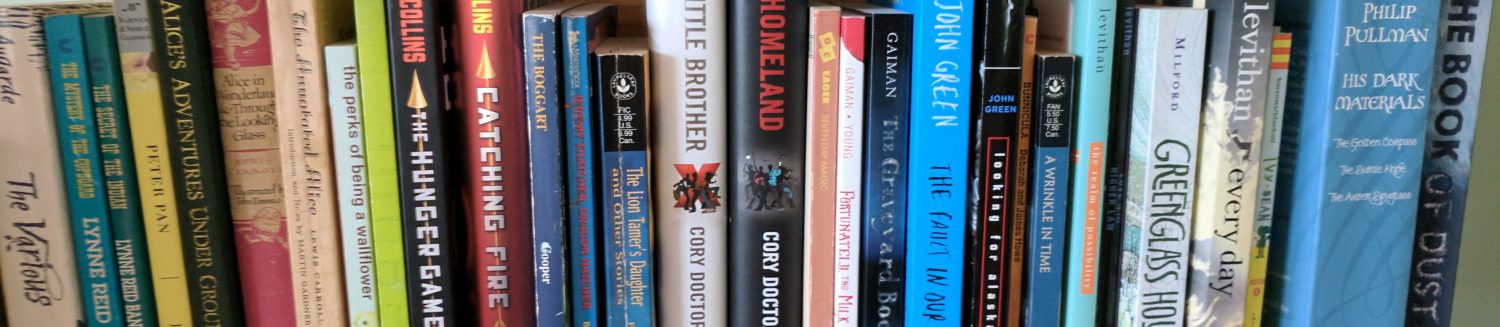

Here’s a good Top Ten Tuesday from The Broke and the Bookish: “Top Ten of Your Auto-Buy Authors.” Like Linda, I don’t necessarily buy all these books, but I am very, very eager to get my hands on them somehow; we’ll call them my “auto-read” authors if not “auto-buy” (though in the case of most of these authors, I have at least one of their books on my home bookshelf. If not all their books. Or in at least one case, multiple copies of the same book).

Ann Patchett: Hands down, Ann Patchett is the first author who comes to mind in this category. I’m still absurdly grateful to the friend at her publisher who got me an advance copy of State of Wonder in February (for my birthday!) when the book didn’t come out till June. I adore everything Ann Patchett writes – fiction, nonfiction, essays, blog posts.

Ann Patchett: Hands down, Ann Patchett is the first author who comes to mind in this category. I’m still absurdly grateful to the friend at her publisher who got me an advance copy of State of Wonder in February (for my birthday!) when the book didn’t come out till June. I adore everything Ann Patchett writes – fiction, nonfiction, essays, blog posts.

Audrey Niffenegger: I’ve already told my husband that when the sequel to The Time Traveler’s Wife comes out (there was a sample – Alba, Continued – included in the e-book version of TTW), I will need a minimum of five days entirely alone with no distractions of any kind. “It’s not going to take you a week to read,” he observed (correctly), but I don’t plan to read it just once. Memorization takes time.

Rainbow Rowell: I have adored all four of her books and am sad that Carry On is embargoed, as it comes out in October of this year and I may be somewhat busy then. (But not too busy to read, right?) Plus, Rebecca Lowman narrates the audiobook versions of Rowell’s books, and that is a match made in heaven.

Rainbow Rowell: I have adored all four of her books and am sad that Carry On is embargoed, as it comes out in October of this year and I may be somewhat busy then. (But not too busy to read, right?) Plus, Rebecca Lowman narrates the audiobook versions of Rowell’s books, and that is a match made in heaven.

David Mitchell: Mitchell’s October book, Slade House, was not embargoed, happily, and I was able to get an e-galley, which I inhaled on vacation last month. I love spending time in his universe. (And yet, still haven’t read Ghostwritten or Number9Dream.)

Maggie O’Farrell: Instructions for a Heatwave sent me scrambling for her backlist, which I quickly read my way through (save one). Cannot wait to read whatever she writes next. Such empathy for all her characters, such heartbreaking plot twists.

Maggie Stiefvater: What an astounding imagination she has. The Scorpio Races is still my favorite, but the Raven Cycle is amazing (still waiting for the fourth and final book!), and she even succeeded with werewolves in the Wolves of Mercy Falls trilogy. I wasn’t as keen on Shiver but am excited to see where she’ll venture next.

Maggie Stiefvater: What an astounding imagination she has. The Scorpio Races is still my favorite, but the Raven Cycle is amazing (still waiting for the fourth and final book!), and she even succeeded with werewolves in the Wolves of Mercy Falls trilogy. I wasn’t as keen on Shiver but am excited to see where she’ll venture next.

Neil Gaiman: Again, I haven’t read everything he’s written, but I have loved all his most recent work (Trigger Warning, The Ocean at the End of the Lane, etc.). (Yes, in this case I’m the person who “discovered” your favorite band long after you knew it was cool.) What Gaiman does with magic and myth is deeply satisfying, original, dark, and timeless.

Tana French: The Likeness is still my favorite, but the Dublin Murder Squad hasn’t dropped off in quality after five books; these mysteries are all deliciously creepy and psychologically dark, with exceptional character development. Plus the covers are gorgeous.

Tana French: The Likeness is still my favorite, but the Dublin Murder Squad hasn’t dropped off in quality after five books; these mysteries are all deliciously creepy and psychologically dark, with exceptional character development. Plus the covers are gorgeous.

Chris Cleave: Just when I was beginning to wonder if/when he would publish a new novel, I see that Everyone Brave is Forgiven is due out in May 2016. I was going to say that I didn’t care what it was about, I was going to read it anyway, but the publisher’s description includes the words “WWII” and “London” and “1939,” so I’m even more hooked. And naturally there is a love triangle.

Nick Laird: I couldn’t possibly buy every book I read, or even every book I love, but I do find that it’s worth it to buy poetry, because (1) someone has to support the poets, and (2) I remember lines and sometimes stanzas but rarely entire poems, and poems are like songs: when parts of them get stuck in your head, the only thing to do is to read/listen to the whole thing. To A Fault, On Purpose, and Go Giants have a permanent place on my bedside bookshelf.

Nick Laird: I couldn’t possibly buy every book I read, or even every book I love, but I do find that it’s worth it to buy poetry, because (1) someone has to support the poets, and (2) I remember lines and sometimes stanzas but rarely entire poems, and poems are like songs: when parts of them get stuck in your head, the only thing to do is to read/listen to the whole thing. To A Fault, On Purpose, and Go Giants have a permanent place on my bedside bookshelf.

Four Americans and the rest English or Irish. Hmm.

I’m sure the moment I publish this I’ll think of at least five more “auto-read” authors, but I feel good about these ten. Also, impatient for their next books.