In the spirit of those sites that do a weekly wrap-up (like Dooce’s “Stuff I found while looking around” and The Bloggess’ “Sh*t I did when I wasn’t here”), here are a few odds and ends I found while going through my work e-mail inbox and my drafts folder.

How to Search: “How to Use Google Search More Effectively” is a fantastic infographic that will teach you at least one new trick, if not several. It was developed for college students, but most of the content applies to everyday Google-users. Google has its own Tips & Tricks section as well, which is probably updated to reflect changes and new features.

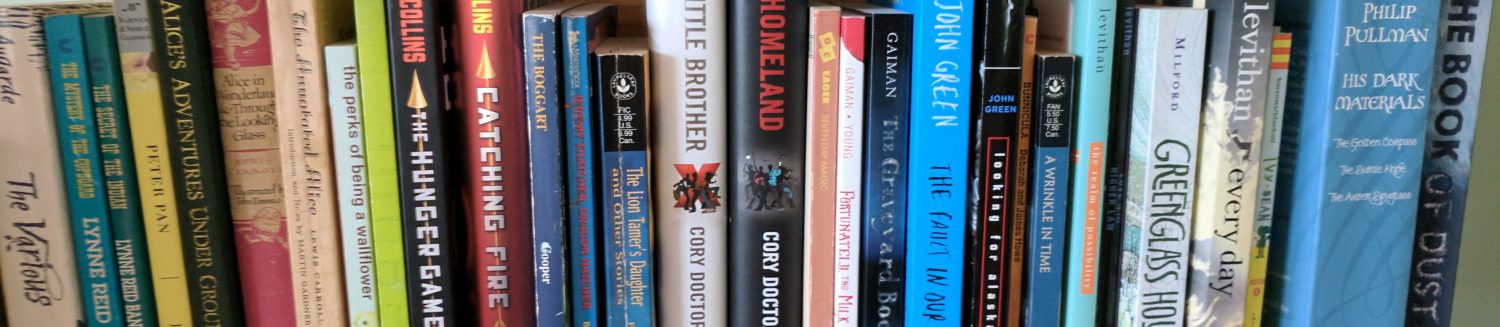

How to Take Care of Your Books: “Dos and Don’ts for Taking Care of Your Personal Books at Home” is a great article by Shelly Smith, the New York Public Library’s Head of Conservation Treatment. Smith recommends shelving your books upright, keeping them out of direct sunlight and extreme temperatures, and dusting. (Sigh. Yes, dusting.)

The ARPANET Dialogues: “In the period between 1975 and 1979, the Agency convened a rare series of conversations between an eccentric cast of characters representing a wide range of perspectives within the contemporary social, political and cultural milieu. The ARPANET Dialogues is a serial document which archives these conversations.” The “eccentric cast of characters” includes Ronald Reagan, Edward Said, Jane Fonda, Jim Henson, Ayn Rand, and Yoko Ono, among others. A gem of Internet history.

All About ARCs: Some librarians over at Stacked developed a survey about how librarians, bloggers, teachers, and booksellers use Advance Reader Copies (ARCs). There were 474 responses to the survey, and the authors summarized and analyzed the results beautifully. I read a lot of ARCs, both in print and through NetGalley or Edelweiss, and I was surprised to learn the extent of the changes between the ARC stage and the finished book; I had assumed changes were copy-level ones, not substantial content-level ones, but sometimes they are. (I also miss the dedication and acknowledgements.)

E-books vs. Print books: There were, at a conservative estimate, approximately a zillion articles and blog posts this year about e-books, but I especially liked this one from The Guardian, “Why ebooks are a different genre from print.” Stuart Kelly wrote, “There are two aspects to the ebook that seem to me profoundly to alter the relationship between the reader and the text. With the book, the reader’s relationship to the text is private, and the book is continuous over space, time and reader. Neither of these propositions is necessarily the case with the ebook.” He continued, “The printed book…is astonishingly stable over time, place and reader….The book, seen this way, is a radically egalitarian proposition compared to the ebook. The book treats every reader the same way.”

On (used) bookselling: This has been languishing in my drafts folder for nearly two years now. A somewhat tongue-in-cheek but not overly snarky list, “25 Things I Learned From Opening a Bookstore” includes such amusing lessons as “If someone comes in and asks for a recommendation and you ask for the name of a book that they liked and they can’t think of one, the person is not really a reader. Recommend Nicholas Sparks.” Good for librarians as well as booksellers (though I’d hesitate to recommend Sparks).

On Libraries: Along the same lines, I really enjoyed Lucy Mangan’s essay “The Rules” in The Library Book. Mangan’s “rules” are those she would enforce in her own personal library, and they include: (2) Silence is to be maintained at all times. For younger patrons, “silence” is an ancient tradition, dating from pre-digital times. It means “the absence of sound.” Sound includes talking. (3) I will provide tea and coffee at cost price, the descriptive terms for which will be limited to “black,” “white,” “no/one/two/three sugars” and “cup.” Anyone who asks for a latte, cappuccino or anything herbal anything will be taken outside and killed. Silently.

On Libraries: Along the same lines, I really enjoyed Lucy Mangan’s essay “The Rules” in The Library Book. Mangan’s “rules” are those she would enforce in her own personal library, and they include: (2) Silence is to be maintained at all times. For younger patrons, “silence” is an ancient tradition, dating from pre-digital times. It means “the absence of sound.” Sound includes talking. (3) I will provide tea and coffee at cost price, the descriptive terms for which will be limited to “black,” “white,” “no/one/two/three sugars” and “cup.” Anyone who asks for a latte, cappuccino or anything herbal anything will be taken outside and killed. Silently.

On Weeding: It’s a truth often unacknowledged that libraries possessed of many books must be in want of space to put them – or must decide to get rid of some. Julie Goldberg wrote an excellent essay on this topic, “I Can’t Believe You’re Throwing Out Books!” I also wrote a piece for the local paper, in which I explain the “culling” of our collection (not my choice of headline).

“What We Talk About When We Talk About Public Libraries”: In an essay for In the Library with the Lead Pipe, Australian Hugh Rundle wrote about the lack of incentives for public librarians to do research to test whether public libraries are achieving their desired outcomes.

Public Journalism, Private Platforms: Dan Gillmor questions how much journalists know about security, and how much control they have over their content once it’s published online. (Article by Caroline O’Donovan at Nieman Journalism Lab)