This is another event that wasn’t on the initial schedule I drew up for myself, but a fellow student-to-staffer (and YALSA member) told me about it, and we went together. I’m so glad I did, especially as I’m taking a young adult literature class this fall; I got a jump on thinking about some of the issues that plague this particular group of readers.

Whose Common Sense?: How Labeling Systems Hurt Young Readers was sponsored by the ALA Intellectual Freedom Committee, and featured four amazing panelists:

Barbara Jones, Director of the ALA Office for Intellectual Freedom, began the session by making the distinction between book reviews and ratings: book reviews treat books as a whole; ratings target elements in books (e.g. sex, violence, etc.). This was perhaps the most objective statement of the whole session, because it was an impassioned session; while some panelists displayed understanding as to where “the other side” was coming from, others did not hold back, though for the most part they were preaching to the choir – librarians generally are for intellectual freedom and readers (of any age) making their own choices, and against censorship.

Michael Norris of Simba offered several statistics, reminding the audience that “not everyone loves books.” In fact, there are 5 print book buyers for every one e-book buyer, and 40% of iPad owners have never bought (or, presumably, read) an e-book. However, he added, censorship is one of the least effective ways to get boys to read books. (Girls are more likely than boys to read on their own.)

Jeffrey Nadel spoke as if he were the nation’s top five debate teams all rolled into one and someone had just hit the two-minute timer. Which is to say: well-spoken, well-rehearsed, articulate, impassioned, persuasive, and armed to the teeth with rhetoric. “What is protection?” he asked, then answered, “A group of people presuming to know better for another group.” In this case, protection is an “intellectual blockade” to exploration and curiosity; Nadel argued that restricting reading can actually harm young people, and that ratings take away freedom and creativity. Young people, he said, are the only protected/regulated “class” in the country, and yet “youth are unique.” He cited the problem with age-based ratings in other forms of media (e.g. movies), which is that “not all 13-year-olds are inherently the same.”

Parents, educators, and anyone with a shred of common sense knows this; one kid might be ready to dive into the Harry Potter series at age 7, while another might not be ready until 10. Christine Jenkins followed this nicely, describing the right and wrong approaches to helping a child find a book. If a kid comes up to the librarian and says, “I need a book,” “How old are you?” is the wrong response; instead, ask “What have you read that you’ve liked?” – just as you would for any other patron. Help with the discovery process, she advised, then let go.

As for ratings and age labels, Jenkins said, they only “give the illusion of control”; furthermore, attitudes shift in response to labels. Yet people are eager to label: the group Parents Against Bad Books in Schools, for example, pays lip service to the idea that “Bad is not for us to determine. Bad is what you determine is bad. Bad is what you think is bad for your child.” That, of course, is followed by a plethora of lists of books with “bad content.”

It’s this kind of mindset that sends David Levithan over the edge. These organizations, companies, and activists – the pro-ratings (and pro-censorship) groups – appear to be nonjudgmental, caring, and objective, but, Levithan said – and he has a point – “you cannot have an objective warning label.” Warning labels imply judgment; warning labels are “the enemy of the truth”; they are devoid of context. “The problem with warning labels,” Levithan said, “is that they’re fucking crazy. They are everything that the freedom to read is NOT about.”

Warning labels are reductive, he argued, and we cannot reduce literature to ratings. In terms of encouraging young people to read, he said, “You have to keep those gates open wide to everything…You can save time [using labels] and end up losing everything.”

All of this occurred before the Q&A session. During the Q&A, one audience member immediately brought up the Wall Street Journal article “Darkness Too Visible,” by Meghan Cox Gurdon, and this topic dominated most of the rest of the time. Gurdon’s article was a protest against the darkness, violence, and “depravity” of young adult literature. She lamented the fact that so many YA books contain “ugliness” and “damage, brutality, and loss.” The article provoked a tremendous reaction; author Sherman Alexie wrote an articulate and passionate defense, also in the WSJ, a few days later (“Why the Best Kids Books Are Written in Blood”).

Alexie was one of the many who spoke out. “When a body of [work/literature] is attacked, the people who it helped come to its defense,” said Levithan. “We are reflecting the problem, not creating it.” Sometimes, the consensus of the session seemed to be, it is better to the let child/young adult experience [fill in the blank] in a book rather than in real life – to have that experience vicariously through the safety of literature. Conversely, for those children and teenagers who have experienced the “dark” subject matter in books in their own lives, they are likely to be comforted, not damaged, by the books – they can empathize with the characters, and know they are not alone. And generally – like any other group of readers – if teens don’t like a book, they will stop reading and put it down.

Another question, after the WSJ article debate, was how to counter the idea that kids need to be protected from ideas. There is a proven link between leisure reading and educational achievement. It is important that kids have access to books that are interesting to them; our role as librarians is to make sure they have that access. Worse than books being challenged is books being censored preemptively – teachers not adding books to their syllabi or librarians not buying books for the library collection because they expect the book to be challenged.

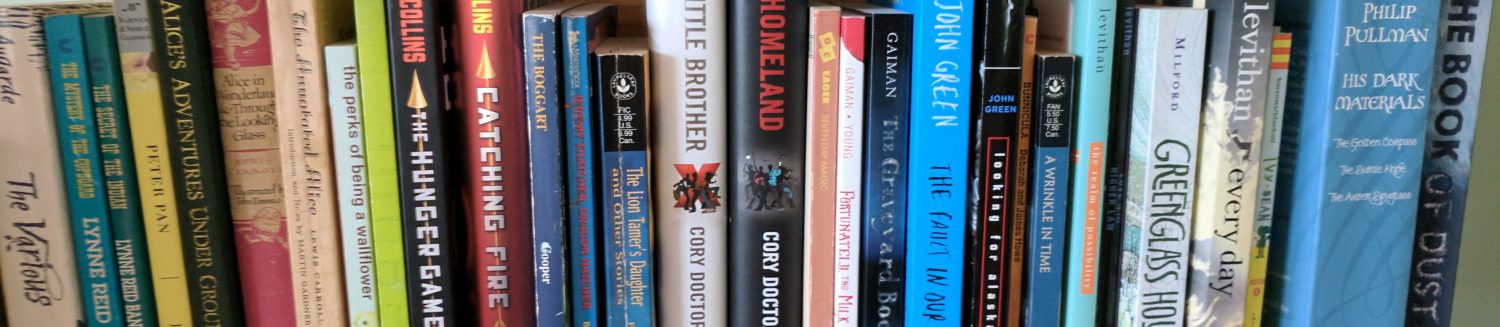

Throughout this panel, I tried to think of a book – any one book, ever – that I had read that had damaged me in some way. I have read over a hundred books a year since grade school, and I know that I have read many of the most frequently banned/challenged books, including more than 30 from each of the most frequently challenged books of the decade lists (1990-1999 and 2000-2009; there’s a lot of overlap). Many of them have been assigned in school – see the list of challenged classics. (Ironically, people have wanted to ban Fahrenheit 451 and 1984 a lot. Bradbury and Orwell would be proud. Or horrified.)

The point is, I couldn’t think of one book I had ever read that I would have preferred to be “protected” from. I’m not a statistically significant sample size, just a case study, but my experience has led me to believe in the freedom to read, for people of all ages. Parents might have the right to determine what their own children are allowed to read, but they should not have the right to determine this for anyone else – not in school libraries, and not in public libraries. Ratings systems make it easier to target those books with “bad content,” and it’s a slippery slope from rating to banning.