Working in a middle school library for the past year, I have been more conscious than ever about what books I am putting into kids’ hands – and, if the match is right, into their heads and hearts. They might read a chapter and put it down, or they might slog through and forget it after they’ve finished a required project…or, they might remember it forever. With that in mind, I (a) always encourage kids to return a book they’re not enthusiastic about and try something else instead, and (b) am extra mindful of representation. When reflect on the books that stayed with me (list below), nearly all of them feature white, American kids, and the few books that centered Jewish characters were all historical fiction set during WWII and the Holocaust (except for Margaret. Thank you, Judy Blume).

- A Wrinkle in Time by Madeleine L’Engle (1962)

- Are You There, God? It’s Me, Margaret by Judy Blume (1970)

- Bridge to Terabithia by Katherine Paterson (1977)

- The Devil in Vienna by Doris Orgel (1978)

- The Castle in the Attic by Elizabeth Winthrop (1985)

- Matilda by Roald Dahl (1988)

- The Devil’s Arithmetic by Jane Yolen (1988)

- Number the Stars by Lois Lowry (1989)

- A Horse Called Wonder (Thoroughbred series #1) by Joanna Campbell (1991)

- The Boggart by Susan Cooper (1993)

- The Giver by Lois Lowry (1993)

- The Golden Compass by Philip Pullman (1995)

- The View from Saturday by E.L. Konigsburg (1996)

It’s a disservice to kids – to any readers – when only “mirrors” books or only “windows” books are available to them. Everyone deserves to see themselves reflected in literature (and art, music, movies, TV, magazines, etc.). The presence of a character similar to you says You exist. You matter. But only reading about characters like yourself is limiting; reading about those who are different in some way provides a window into another way of experiencing the world: They exist. They matter.

I have read so many middle grade books in the past few years that I couldn’t have imagined existing a generation ago. There are books with trans and non-binary characters, like Kyle Lukoff’s Different Kinds of Fruit and Too Bright to See and Ami Polonsky’s Gracefully Grayson and Alex Gino’s Melissa. There are books with Muslim protagonists by S.K. Ali and Saadia Faruqi, Hena Khan and Veera Hiranandani, and books with Latinx characters like Meg Medina’s Merci Suárez, Celia Pérez’s The First Rule of Punk, and Pablo Cartaya’s Marcos Vega Doesn’t Speak Spanish. There are books that address contemporary racism and microaggressions and police violence, like Blended by Sharon Draper. There are books by and about Indigenous people, like Rez Dogs by Joseph Bruchac and Ancestor Approved by Cynthia Leitich Smith and others. There are books that explore the histories and modern experiences of Asian American and Pacific Islanders, like Finding Junie Kim by Ellen Oh, Other Words for Home by Jasmine Warga, and Inside Out & Back Again by Thanhha Lai – the last two of which are in verse, a form I never encountered as a young reader but which is becoming more and more popular now (and with good reason). There are books about fat-shaming and fatphobia and body positivity, books that show what good therapy looks like, characters who experience mental illness or poverty, frank discussion of periods and endometriosis, and activism.

There is nothing inherently bad about the books I read and loved as a kid; I still re-read and love them, and am starting to share them with my daughter (and discuss parts that are sexist, racist, or otherwise problematic). But as a collection, they don’t show the dazzling breadth and depth of human experience that children’s literature illuminates now, from picture books through middle grade to young adult. I am so grateful to the authors and illustrators who create these works, let readers step into their characters’ shoes, learn about their lives, and grow in empathy, and I feel lucky to be able to put these books into kids’ hands.

Big thanks to the children’s librarians at the Newton Free Library for organizing, promoting, hosting, and moderating a delightful

Big thanks to the children’s librarians at the Newton Free Library for organizing, promoting, hosting, and moderating a delightful

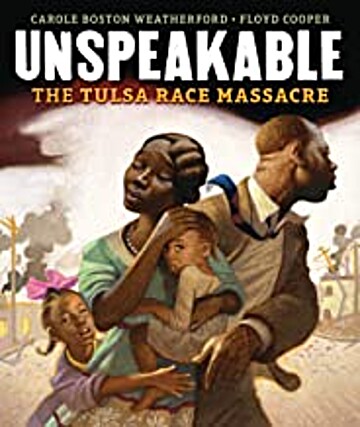

I can’t imagine anyone was surprised that Unspeakable by Carole Boston Weatherford, illustrated by Floyd Cooper, won two Coretta Scott King awards (for author and for illustrator), as well as a Sibert honor and a Caldecott honor. I’m looking forward to reading CSK illustrator honor book Nina, but I’m really surprised that Christian Robinson’s other 2021 book, Milo Imagines the World, didn’t get any official recognition.

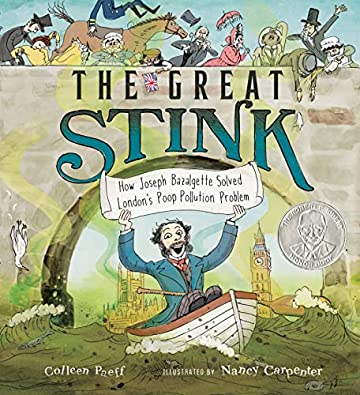

I can’t imagine anyone was surprised that Unspeakable by Carole Boston Weatherford, illustrated by Floyd Cooper, won two Coretta Scott King awards (for author and for illustrator), as well as a Sibert honor and a Caldecott honor. I’m looking forward to reading CSK illustrator honor book Nina, but I’m really surprised that Christian Robinson’s other 2021 book, Milo Imagines the World, didn’t get any official recognition. I’d actually read a bunch of Sibert honor books, though not the winner; I was super excited to see The Great Stink on the list. We Are Still Here by Traci Sorrell and Unspeakable also got honors, as did Summertime Sleepers (which taught me the word “estivate,” which is like hibernating but in the summer).

I’d actually read a bunch of Sibert honor books, though not the winner; I was super excited to see The Great Stink on the list. We Are Still Here by Traci Sorrell and Unspeakable also got honors, as did Summertime Sleepers (which taught me the word “estivate,” which is like hibernating but in the summer).

I’ve been following Eula Biss’s writing since I got a galley of On Immunity: An Inoculation back in 2014 (she said during this interview that she “would love for that book to become obsolete,” but if you know anyone asking themselves “to vaccinate or not to vaccinate?” please buy them a copy). Eula joined writing instructor and Emerita Senior Faculty Associate Deb Gorlin to discuss her writing career and her newest book, Having and Being Had.

I’ve been following Eula Biss’s writing since I got a galley of On Immunity: An Inoculation back in 2014 (she said during this interview that she “would love for that book to become obsolete,” but if you know anyone asking themselves “to vaccinate or not to vaccinate?” please buy them a copy). Eula joined writing instructor and Emerita Senior Faculty Associate Deb Gorlin to discuss her writing career and her newest book, Having and Being Had.

If we’ve met in real life, probably I have talked your ear off about Kate Milford’s Greenglass House books. Her kind of world-building is one of my favorite kinds: our world, but different. And the ways that it’s different are so inventive and compelling to me, from Nagspeake’s shifting iron and the Skidwrack river to the existence of roamers, a culture of smuggling, and an evil catalog company. Plus, the structure of her books is excellent, and nearly always features an ensemble cast of interesting characters, many of whom cross between books – basically, David Mitchell for middle grade, but completely her own. And her newest book, The Raconteur’s Commonplace Book, is actually the book that Milo (main character of Greenglass House) reads – so Kate invented a book-within-a-book, then wrote that book. And like Greenglass House, it’s an Agatha Christie-style strangers-stuck-in-a-house-together setup.

If we’ve met in real life, probably I have talked your ear off about Kate Milford’s Greenglass House books. Her kind of world-building is one of my favorite kinds: our world, but different. And the ways that it’s different are so inventive and compelling to me, from Nagspeake’s shifting iron and the Skidwrack river to the existence of roamers, a culture of smuggling, and an evil catalog company. Plus, the structure of her books is excellent, and nearly always features an ensemble cast of interesting characters, many of whom cross between books – basically, David Mitchell for middle grade, but completely her own. And her newest book, The Raconteur’s Commonplace Book, is actually the book that Milo (main character of Greenglass House) reads – so Kate invented a book-within-a-book, then wrote that book. And like Greenglass House, it’s an Agatha Christie-style strangers-stuck-in-a-house-together setup. Melissa Albert pulled off a similar trick with Tales of the Hinterland, which she first dreamed up within the context of The Hazel Wood. Tales is a book of dark fairytales that is out of print and hard to access, adding to its mystery and allure. As a reader and a writer, I am in awe: it’s hard enough to invent a creative work that exists for your characters within the world of the book, like Nick Hornby does in Juliet, Naked and David Mitchell does in Utopia Avenue. This piece of art exists for the characters, and grows in the reader’s imagination until it has nearly mythological status. So then, to write that book – and have it meet or exceed expectations – takes immense bravery and talent. Brava!

Melissa Albert pulled off a similar trick with Tales of the Hinterland, which she first dreamed up within the context of The Hazel Wood. Tales is a book of dark fairytales that is out of print and hard to access, adding to its mystery and allure. As a reader and a writer, I am in awe: it’s hard enough to invent a creative work that exists for your characters within the world of the book, like Nick Hornby does in Juliet, Naked and David Mitchell does in Utopia Avenue. This piece of art exists for the characters, and grows in the reader’s imagination until it has nearly mythological status. So then, to write that book – and have it meet or exceed expectations – takes immense bravery and talent. Brava!