On October 6, Nate Hoffelder wrote a post on The Digital Reader: “Adobe is Spying on Users, Collecting Data on Their eBook Libraries.” (He has updated the post over the past couple days.) Why is this privacy-violating spying story any more deserving of attention than the multitude of others? For librarians and library users, it’s important because Adobe Digital Editions is the software that readers who borrow e-books from the library through Overdrive (as well as other platforms) are using. This software “authenticates” users, and this is necessary because the publishers require DRM (Digital Rights Management) to ensure that the one copy/one user model is in effect. (Essentially, DRM allows publishers to mimic the physical restrictions of print books – i.e. one person can read a book at a time – on e-books, which could technically be read simultaneously by any number of people. To learn more about DRM and e-books, see Cory Doctorow’s article “A Whip to Beat Us With” in Publishers Weekly; though now more than two years old, it is still accurate and relevant.)

So how did authentication become spying? Well, it turns out Adobe was collecting more information than was strictly necessary, and was sending this information back to its servers in clear text – that is, unencrypted. Sean Gallagher has been following this issue and documenting it in Ars Technica (“Adobe’s e-book reader sends your reading logs back to Adobe – in plain text“). According to that piece, the information Adobe says it collects includes the following: user ID, device ID, certified app ID, device IP address, duration for which the book was read, and percentage of the book that was read. Even if this is all they collect, it’s still plenty of information, and transmitted in plain text, it’s vulnerable to any other spying group that might be interested.

The plain text is really just the icing on this horrible, horrible cake. The core issue goes back much further and much deeper: as Andromeda Yelton wrote in an eloquent post on the matter, “about how we default to choosing access over privacy.” She points out that the ALA Code of Ethics states, “We protect each library user’s right to privacy and confidentiality with respect to information sought or received and resources consulted, borrowed, acquired or transmitted,” and yet we have compromised this principle so that we are no longer technically able to uphold it.

Jason Griffey responded to Yelton’s piece, and part of his response is worth quoting in full:

“We need to decide whether we are angry at Adobe for failing technically (for not encrypting the information or otherwise anonymizing the data) or for failing ethically (for the collection of data about what someone is reading)….

…We need to insist that the providers of our digital information act in a way that upholds the ethical beliefs of our profession. It is possible, technically, to provide these services (digital downloads to multiple devices with reading position syncing) without sacrificing the privacy of the reader.”

Griffey linked to Galen Charlton’s post (“Verifying our tools; a role for ALA?“), which suggested several steps to take to tackle these issues in the short term and the long term. “We need to stop blindly trusting our tools,” he wrote, and start testing them. “Librarians…have a professional responsibility to protect our user’s reading history,” and the American Library Association could take the lead by testing library software, and providing institutional and legal support to others who do so.

Charlton, too, pointed back to DRM as the root of these troubles, and highlighted the tension between access and privacy that Yelton mentioned. “Accepting DRM has been a terrible dilemma for libraries – enabling and supporting, no matter how passively, tools for limiting access to information flies against our professional values. On the other hand, without some degree of acquiescence to it, libraries would be even more limited in their ability to offer current books to their patrons.”

It’s a lousy situation. We shouldn’t have to trade privacy for access; people do too much of that already, giving personal information to private companies (remember, “if you’re not paying for a product, you are the product“), which in turn give or sell it to other companies, or turn it over to the government (or the government just scoops it up). In libraries, we still believe in privacy, and we should, as Griffey put it, “insist that the providers of our digital information act in a way that upholds the ethical beliefs of our profession.” It is possible.

10/12/14: The Swiss Army Librarian linked to another piece on this topic from Agnostic, Maybe, which is worth a read: “Say Yes No Maybe So to Privacy.”

10/14/14: The Waltham Public Library (MA) posted an excellent, clear Q&A about the implications for patrons, “Privacy Concerns About E-book Borrowing.” The Librarian in Black (a.k.a. Sarah Houghton, Director of the San Rafael Public Library in California), also wrote a piece: “Adobe Spies on eBook Readers, including Library Users.” The ALA response (and Adobe’s response to the ALA) can be found here: “Adobe Responds to ALA on egregious data breach,” and that links to LITA’s post “ADE in the Library Ebook Data Lifecycle.”

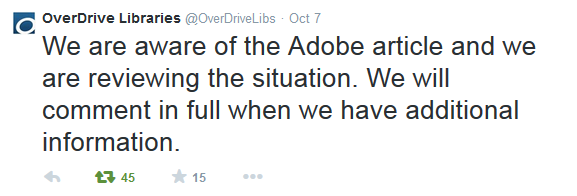

10/16/14: “Adobe Responds to ALA Concerns Over E-Book Privacy” in Publishers Weekly; Overdrive’s statement about adobe Digital Editions privacy concerns. On a semi-related note, Glenn Greenwald’s TED talk, “Why Privacy Matters,” is worth 20 minutes of your time.

[…] “(Failing to) Protect Patron Privacy” by Jenny Arch […]

Did you hear Anil Dash’s closing keynote at last week’s Digital Shift conference, and/or see the reaction on Twitter? He really struck a chord with his librarian audience, and it’s resonating ever more this week, as this “lousy situation” unfolds.

I did not, but I am going to go look it up right now. Thanks!

Anil Dash at #TDS14: http://www.thedigitalshift.com/2014/10/social-media/anil-dash-keynote-rallies-librarians-demand-web-people-tds14/