I have spent my whole life in the world of books. I was lucky; my parents read to me every night while I was growing up, from before I could talk until the night I took the book away and started reading it myself, because that was faster and I wanted to know what happened next. I was lucky, and I took that luck and ran with it: I’ve spent the last six years officially in book world, first in publishing, now in libraries.

Over the years, I have identified a few heroes, here in Book World: these people are authors, yes, but they are also, variously, library advocates, booksellers, privacy experts, generous public speakers, tirelessly creative, funny, kind, intelligent, empathetic. (At least, they are all of these things as far as I can tell.)

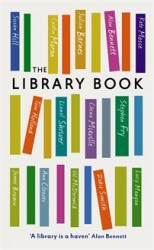

I’ve written about them all here before: Cory Doctorow, Ann Patchett, and Neil Gaiman. But the latter has gone and given another brilliant talk, so I must write about him again. An edited version of this talk, which Gaiman gave for The Reading Agency, was published in The Guardian. (Not coincidentally, The Reading Agency is the organization that The Library Book – not the easiest title to find, but well worth it – was published in aid of.)

I’ve written about them all here before: Cory Doctorow, Ann Patchett, and Neil Gaiman. But the latter has gone and given another brilliant talk, so I must write about him again. An edited version of this talk, which Gaiman gave for The Reading Agency, was published in The Guardian. (Not coincidentally, The Reading Agency is the organization that The Library Book – not the easiest title to find, but well worth it – was published in aid of.)

In his “impassioned plea” to support libraries and librarians, Gaiman spoke about the importance of literacy, and the role of fiction in fostering literacy. Fiction, he said, “is a gateway drug to reading.” He said,

“The simplest way to make sure that we raise literate children is to teach them to read, and to show them that reading is a pleasurable activity. And that means, at its simplest, finding books that they enjoy, giving them access to those books, and letting them read them.

I don’t think there is such a thing as a bad book for children. Every now and again it becomes fashionable among some adults to point at a subset of children’s books, a genre, perhaps, or an author, and to declare them bad books, books that children should be stopped from reading. I’ve seen it happen over and over; Enid Blyton was declared a bad author, so was RL Stine, so were dozens of others. Comics have been decried as fostering illiteracy.

It’s tosh. It’s snobbery and it’s foolishness. There are no bad authors for children, that children like and want to read and seek out, because every child is different. They can find the stories they need to, and they bring themselves to stories. A hackneyed, worn-out idea isn’t hackneyed and worn out to them. This is the first time the child has encountered it. Do not discourage children from reading because you feel they are reading the wrong thing.”

Banned Book Week is still fresh in many librarians’ minds just now; it’s when we encourage everyone to celebrate the freedom to read. Some kids want to read Batman comics, some want to read Calvin & Hobbes, some want to read The Lion, The Witch, and the Wardrobe or Pride and Prejudice or The Catcher in the Rye or Twilight or The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy. Let them; it won’t hurt. And once they love reading, once they want to know what happens next, maybe they’ll discover new books and new genres – but they’re much more likely to pick up a second book if they liked the first one.

Gaiman also discussed the relationship between fiction and empathy, which has been studied and written about recently. (There are several links in this Banned Books Week post about censorship.) Gaiman explains just how prose fiction stretches the imagination in ways that film does not:

“And the second thing fiction does is to build empathy. When you watch TV or see a film, you are looking at things happening to other people. Prose fiction is something you build up from 26 letters and a handful of punctuation marks, and you, and you alone, using your imagination, create a world and people it and look out through other eyes. You get to feel things, visit places and worlds you would never otherwise know. You learn that everyone else out there is a me, as well. You’re being someone else, and when you return to your own world, you’re going to be slightly changed.

Empathy is a tool for building people into groups, for allowing us to function as more than self-obsessed individuals….Fiction can show you a different world. It can take you somewhere you’ve never been. Once you’ve visited other worlds, like those who ate fairy fruit, you can never be entirely content with the world that you grew up in. Discontent is a good thing: discontented people can modify and improve their worlds, leave them better, leave them different.”

So: fiction leads to empathy as well as literacy. And literacy “is more important than ever it was, in this world of text and email, a world of written information. We need to read and write, we need global citizens who can read comfortably, comprehend what they are reading, understand nuance, and make themselves understood.”

Where then is one to acquire all this nutritious and delicious fiction? The library, of course. But the library, unfortunately, is frequently under attack, less from outright anti-library sentiment than from a need to cut municipal, state, or federal budgets. This problem isn’t specific to the U.S.; it’s just as bad, if not worse, in the U.K. Closing libraries, though, is shortsighted in a society that, presumably, wants literate, engaged, imaginative, problem-solving citizens:

“Libraries really are the gates to the future. So it is unfortunate that, round the world, we observe local authorities seizing the opportunity to close libraries as an easy way to save money, without realising that they are stealing from the future to pay for today. They are closing the gates that should be open….We have an obligation to support libraries. To use libraries, to encourage others to use libraries, to protest the closure of libraries. If you do not value libraries then you do not value information or culture or wisdom. You are silencing the voices of the past and you are damaging the future.”

For most of his talk, Gaiman was speaking as a reader, but he is also an author (quite a prolific one). He spoke out powerfully about writers’ obligations to their readers – what to do and what not to do:

“We writers – and especially writers for children, but all writers – have an obligation to our readers: it’s the obligation to write true things, especially important when we are creating tales of people who do not exist in places that never were – to understand that truth is not in what happens but what it tells us about who we are. Fiction is the lie that tells the truth, after all. We have an obligation not to bore our readers, but to make them need to turn the pages. One of the best cures for a reluctant reader, after all, is a tale they cannot stop themselves from reading. And while we must tell our readers true things and give them weapons and give them armour and pass on whatever wisdom we have gleaned from our short stay on this green world, we have an obligation not to preach, not to lecture, not to force predigested morals and messages down our readers’ throats like adult birds feeding their babies pre-masticated maggots; and we have an obligation never, ever, under any circumstances, to write anything for children that we would not want to read ourselves.”

This single paragraph gets at the heart of reading and writing, fiction and truth. We have an obligation to write true things…when we are creating tales of people who do not exist in places that never were. Truth is not in what happens but that it tells us about who we are.

My friend Kelly just co-wrote an article for the YALSA (Young Adult Library Services Association) blog that explores the common prejudice against fantasy and science fiction. She and her co-author make a strong case for these genres, and arrive at the same conclusion as Gaiman: “The way that we receive guidance from books is not a literal process. We are influenced by something much deeper in literature, which is the connections we share as humans and the ways in which some experiences are unique, and some are universal.” All fiction, whether it’s realistic or fantastical, stretches the reader’s imagination and builds empathy.

Gaiman’s final point – “We have an obligation never…to write anything for children that we would not want to read ourselves” – is important, too, and it explains why so many adults have not just lingering nostalgia for the books they loved as children, but a fierce love for them, and even an interest in reading them still. Many, many grown-up readers today are passionate about YA fiction (despite some others’ judgment on the matter); the people waiting for the library copies of Every Day by David Levithan, The Fault in Our Stars by John Green, Fangirl by Rainbow Rowell – not to mention the dystopian trilogies by Suzanne Collins (The Hunger Games, etc.) and Veronica Roth (Divergent, etc.) – aren’t all teenagers.

If all of this isn’t a strong enough argument for reading and libraries, check out Amanda Ripley’s The Smartest Kids in the World: And How They Got That Way. I’ll give you a hint: their parents read to them.

[…] of ideas, freedom of communication…Libraries really are the gates to the future.” [I wrote about this same speech at length soon after it was published online by The […]

[…] reminded me a bit of the way Neil Gaiman talks about fiction (“Fiction can show you a different world. It can take you somewhere you’ve never […]

[…] reminded me of what Neil Gaiman had to say on the topic of fiction and empathy. I’ve quoted from this speech of his before, but here it is again, slightly […]

“Fiction is the lie that tells the truth” – Albert Camus said that first.

I’m curious, what’s your source for this? I’ve checked the Yale Book of Quotations and Bartlett’s Familiar Quotations and neither of those sources attribute the quote to Camus.

It is his The Outsider manuscript – handwritten stuff.

It says “Fiction is the lie through which we tell the truth”.

Thanks.