In January, the Youth Services Interest Group (YSIG) hosted librarian Rhonda Cunha to present on the topic “Understanding Literacy Acquisition for Targeted Reader’s Advisory” at the Woburn Public Library. Rhonda is the Early Literacy Children’s Librarian at the Stevens Memorial Library in Andover, MA, and her presentation was detailed and thorough. I’m going to try to condense six pages of notes into a coherent overview here, starting with an important definition:

Reading is making meaning from text.

In the public library, Rhonda often overheard misconceptions about how children learn to read; her presentation corrects some of those misunderstandings. As children’s librarians, we are ideally placed to promote literacy, help children love reading, and help parents.

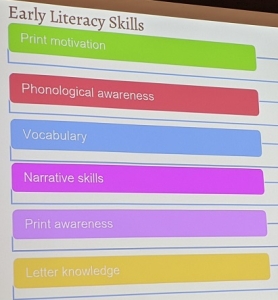

Early literacy skills include print motivation, phonological awareness, vocabulary, narrative skills (storytelling), print awareness (how books work), and letter knowledge. Two major ways that public libraries help children develop early literacy skills are through storytime programs and readers’ advisory services: talking with readers and helping them find books they’ll love (ideally, talking directly with the kids; talking with the parents is second best).

Readers’ advisory is more complex for children than for adults, because they are still developing these literacy skills: the book’s content needs to be interesting to them, and the book needs to be the right level. However, we don’t “level” books in the public library, for several reasons. Part of helping kids see themselves as readers and develop a love of reading is supporting them, not labeling them. (Benchmarking is a teaching tool for teachers to evaluate what the kids know, determine the point of need, and enable them to teach to the child’s need. “Levels” – Lexile and Fountas & Pinnell are two common ones – should not be shared with the kids themselves, let alone their parents.) A young reader’s background knowledge might enable them to read a book more advanced than their designated “level,” or they might want to pick up a book that’s easier – and that’s fine.

How to Help Kids Choose Just-Right Books for Them:

- Helping children develop independent reading identities requires respect, trust, and lots of patience.

- Encourage kids to vary their reading diet, in terms of genres and interests. Give them what they want, and slip in a few extras.

- Provide lots of choices.

- Encourage them to abandon books that don’t “sing” to them: “Good readers abandon books!” If you don’t like it, don’t read it. (But give it a chance – start with 10-20 pages, and if you don’t like it, stop. This goes for adult readers, as well.)

- Use the 5-finger rule. Open a book to a page and start reading; put a finger up for each word they don’t know. (1=easy, 2=still easy, 3=okay, 4=challenging, 5=too hard)

- Knowing what they don’t like is as important as knowing what they do like.

- Use the acronym BOOKMATCH: Book length, Ordinary language, Organization, Knowledge prior to book, Manageable text, Appeal to genre, Topic appropriateness, Connection, High interest

Self-efficacy is key! Children need to see themselves as capable readers and to believe they can succeed. There are four steps to self-efficacy:

- Mastery experiences (reading to themselves without difficulty)

- Social models (seeing adults reading and writing)

- Social persuasion (encouragement and cheerleading, “I know you can do it!”)

- Mood

“While children are learning the skills of reading, they must also develop a positive reading identity or they will not become lifelong readers.” –Donalyn Miller

Advice for Parents:

- Reading aloud to children builds receptive vocabulary, which becomes expressive vocabulary. Additionally, kids’ listening comprehension level is usually higher than their reading (print) comprehension. Reading aloud is the most important thing parents can do!

- Social modeling: Kids should see their parents reading and writing (writing grocery lists, to-do lists, thank you notes, etc.).

- Read familiar books to keep success high. (“If they want to read Wimpy Kid sixteen times, let them!”) Read predictable, repeating texts and short books. Read the books they bring home from school to bolster confidence.

- Make reading a special daily ritual – try for at least 20 minutes a day/night.

- Keep it fun and positive. Balance corrections with story flow (focus on one thing each time). If the kid is reading aloud and gets stuck on a word, count to 5 (silently) and supply the word so they can move on.

- Name the strategies they are using.* Reread the same sentence/book if decoding is slow. Use the language that the school uses when recognizing strategies.

- Readers who self-correct are checking for comprehension (this is good!).

- Be aware of cognitive overload** – it’s okay to take over. Make them happy about reading/being read to.

- End on a positive note.

*Recently, I was reading Jenny and the Cat Club by Esther Averill to my four-year-old, and we came across the word “weary.” I asked her if she knew what it meant, and she said no. I read the whole sentence again, and asked her to guess what it meant. “Tired?” She got it! I was so excited. I explained that what she’d just done was figure out the meaning of a word from context – the words around that word. She was really pleased and proud.

**Cognitive capacity: you have X amount. How much are you using for decoding, how much for comprehension? Accuracy and fluency are important, so readers aren’t using all their cognitive capacity for decoding. Phonics will only get you so far; 40% of the words in English cannot be decoded.

Reading is making meaning from text, so how do we learn to do that? Here are some decoding strategies used in school:

- Ask: Does that look right? Does it sound right? Does it make sense?

- Get your mouth ready to say that word. Skip the word and read around it (to get context – see above).

- Ask: What would fit there?

- Break the word up into smaller known words or sounds (families, blends, compounds).

- Look at the picture for clues (Cunha said, “There are pictures in books for a reason! There is no cheating in reading”).

- Before you start reading:

- Activate prior knowledge (e.g., “What do we already know about dolphins?” Look at the book’s cover – what do you see, what do you notice?)

- Preview difficult or unknown vocabulary and/or take a picture walk.

- Be present to notice behaviors, give support, and watch for burnout.

More advice and strategies for reading and reading together:

- As books become more advanced, cognitive demands on the readers increase. The more a kid has in their head already, the less dependent on the text they are (top-down vs. bottom-up processing).

- The way children acquire language is through a direct connection with people they’re conversing with (“serve and return” communication).

- When a kid reads aloud, you hear their mistakes, which are informative; in order to teach, you have to hear the errors.

- Monitor for meaning: Ask big-picture questions, not detail questions (e.g. “How do you think he felt?” vs. “What color was his shirt?”)

Want to learn more? See below for more resources.

Recommended reading:

Recommended reading:

The Reading Zone: how to help kids become skilled, passionate, habitual, critical readers by Nancie Atwell

Readicide by Kelly Gallagher

The Enchanted Hour by Meghan Cox Gurdon

The Book Whisperer by Donalyn Miller

Reading Picture Books With Children by Megan Dowd Lambert

The Read-Aloud Handbook by Jim Trelease

BOOKMATCH: How to Scaffold Student Book Selection for Independent Reading by Linda Wedwick and Jessica Ann Wutz

Reading teacher newsletter from International Literacy Association: https://www.literacyworldwide.org/

“Learning, Interrupted: Cell Phone Calls Sidetrack Toddlers’ Word Learning,” American Psychological Association, November 21, 2017

“Thinking Outside the Bin: Why Labeling Books By Reading Level Disempowers Young Readers,” Kiera Parrott, School Library Journal, August 28, 2017