You know when you are talking with someone and suddenly you wonder, “Wait, how did we get on this subject?” I like to be able to trace back to the original subject, as a kind of memory exercise. When the “conversation” isn’t with a person but is just you clicking from link to link on the Internet, the trail is a little easier to follow, thanks to tabs and the browser’s back button. Here was my path this morning:

- Today’s Library Link of the Day, “Wanted: The New Librarian of Congress,” by Andy Woodworth on the blog I Need a Library Job (INALJ). I always click through to the Library Link of the Day, even if I don’t end up reading the source (depends if it’s relevant/interesting to me), but I’ve been following the #nextLoC issue via Jessamyn West on Twitter and her blog.

- At the bottom of the article was a link to Andy’s own blog, Agnostic, Maybe, which I knew I’d visited before but don’t follow regularly, so I clicked through to see what he’d been writing about recently.

- His most recent post, “OIF & 538,” referenced a previous Library Link of the Day from June 24, 2015, which I remembered reading, but wanted to refresh my memory. (The Library Link of the Day helpfully keeps archives by date, but Andy also linked to the post he referenced.)

- The piece in FiveThirtyEight was called “We Tried – And Failed – To Identify the Most Banned Book in America.”

All of the above links are worth reading, so I’ll only offer a very brief summary, and a few thoughts. The author of the 538 article, David Goldenberg, expressed frustration that (a) the ALA Office of Intellectual Freedom (OIF) would not hand over the raw data they collect on book challenges, and that (b) the quality of the data presented on the ALA’s site was not particularly granular or detailed and may not be statistically valid. For instance, a “challenge” might be a request to move a book from the children’s collection to the teen or adult collection, or it may be a demand that all copies of a book be removed from an entire library system. There’s a big difference between those two challenges.

In his reply to the 538 piece, Andy Woodworth delves into some of the issues behind challenge reporting and data collection. He writes that students in library school don’t learn they have an obligation to report challenges, that there may be external pressures not to report challenges, and that librarians simply may not know to report challenges. If they do report a challenge, though, there are more problems with the ALA-OIF itself: the amount of information required in the online challenge form is minimal, and the OIF does not have the budget or staff to chase down details or outcomes from the challenges that are reported. (The challenge form is also available as a PDF that can be printed, filled out, and faxed to the OIF. It’s certainly possible to find an e-mail address for someone at the OIF, but shouldn’t this be included as an option on the form?)

While I was in library school, I learned about the ALA’s Sample Request for Reconsideration of Library Resources, a form that can be adapted by any library and kept on hand in case of challenges. At both of the public libraries where I’ve worked, we have had this form ready to hand (though in my experience, challenges are exceedingly rare, at least at the adult reference desk; this is borne out by the ALA data – and many media reports – that show more challenges happen in school libraries than in public ones).

Should someone come to the reference desk with a challenge, I would be prepared with the reconsideration form. But what the form lacks, I noticed after reading Andy’s piece, is anything about reporting the challenge to the OIF. (On Twitter, Andy said he wrote it into the reconsideration policy at his library that “we reserve discretion to report challenges to the OIF.”) I don’t think it would hurt for library patrons to be aware of that, and it would remind library staff to take the extra step to report challenges when they do occur.

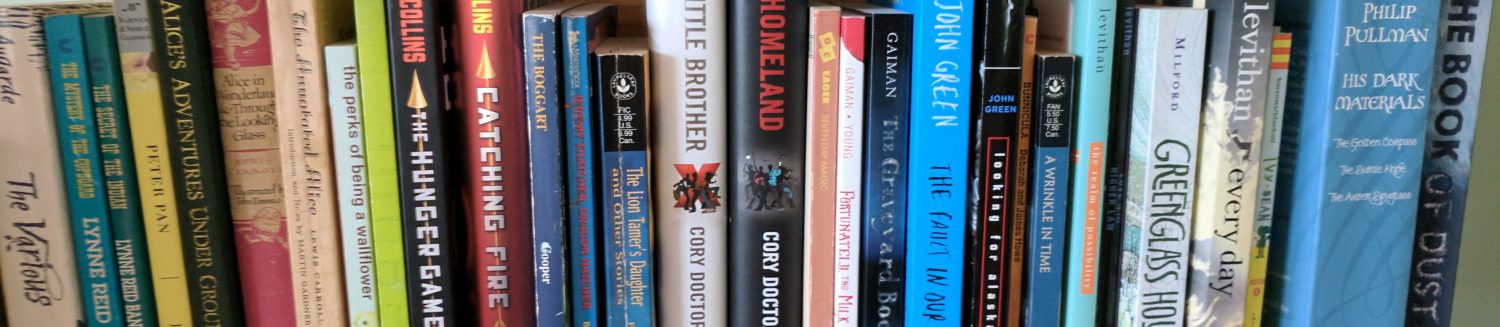

The granularity of the reporting, as Andy, David, and Jessamyn all pointed out, still leaves something to be desired. Every September, I put together a Banned Books Week display in the library and write about banned/challenged books and the freedom to read on the library blog. Every year, I’m frustrated by the ALA website, which, despite a redesign within the past five years, does not adhere to many of the web conventions and usability guidelines outlined in Useful, Usable, Desirable by Aaron Schmidt and Amanda Etches (about which more soon). The information architecture is convoluted and fragmented – there’s information on the ALA main site and a separate Banned Books Week website – the presentation isn’t as clear and attractive as it could be, and despite the existence of both sites, neither usually has the quality of data I want to present to our library patrons.

Both of these problems – the information itself and the organization of information – are especially vexing because information and organization is what we do. Furthermore, intellectual freedom is a core value of the library profession; Article II of the ALA Code of Ethics is “We uphold the principles of intellectual freedom and resist all efforts to censor library resources.” We need to do better, and it shouldn’t be that hard. We need to:

- Raise awareness among library staff that reporting challenges is important and that there are ways to do it confidentially.

- Collect more detailed data when possible and present it in as granular a fashion as possible, noting if necessary that not all reported challenges include the same level of detail.

It’s not rocket science. What are we waiting for?

This is good thinking. I would just clarify that 1963 saw the last book banned in the USA. As Jessamyn West said, keeping kids from inappropriate books is a very serious issue, but it’s not the same as book banning. As Judith Krug said, in the rare instance a book does not meet its school collection policy, “get it out of there.” Certainly Judith Krug is no book banner. So my suggestion would be to drop the language about “banned” books, except where it cannot be avoided, such as referring to “Banned Books Week.”

True, books aren’t so much “banned” now as “challenged”; Jessamyn West addresses the misnomer in her post about Banned Books Week (http://www.librarian.net/stax/1858/banned-books-week-is-next-week/). There is often a valid argument for moving a book from one section of a library to another, but not for removing it completely. (Weeding is another story! Getting rid of outdated medical books is generally a good idea 🙂